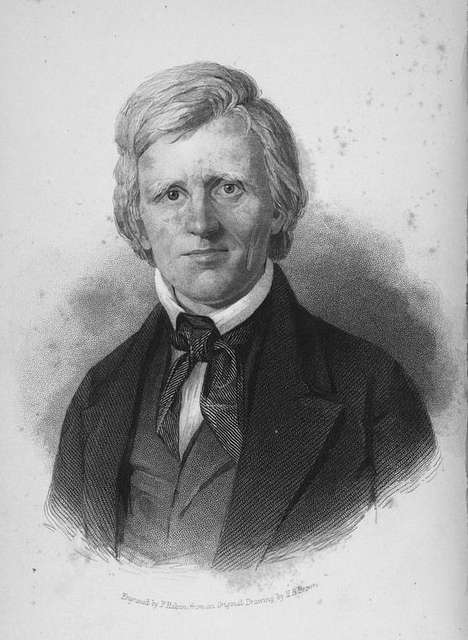

Nathaniel Peabody Rogers

Born in Plymouth in 1794, Nathaniel Peabody Rogers abandoned a successful legal career for a position as editor of a radical anti-slavery newspaper, Herald of Freedom, which he ran until he lost his position in a factional dispute with other abolitionists. During his time at the helm of the paper, Herald of Freedom was a leading voice for the abolition of slavery and establishment of full equality.

After exposure to the ideas of William Lloyd Garrison in the early 1830s, Rogers threw himself into the abolition movement. He formed the Plymouth Anti Slavery Society in 1833 and was among the founders of the NH Anti Slavery Society the next year. His wife, Mary, headed the Plymouth Female Anti Slavery Society; their home in Plymouth was a stopover for traveling abolitionist lecturers like Garrison, the poet John Greenleaf Whittier, and British activist George Thompson. It is also known to have been a “safe house” on the Underground Railroad. Rogers was a trustee at Noyes Academy during its short existence and wrote articles for Herald of Freedom.

In 1838, the Rogers family moved to Concord, where he took over Herald of Freedom. It was not only a farewell to a lucrative career for one with little prospect of financial success, it was also a position with considerable risk. Radical abolitionists of the 1830s knew they could come under violent attack, and the editors of abolitionist newspapers were among the most visible and vulnerable. The story of Elijah Lovejoy, an abolitionist publisher who was murdered in Illinois in 1837, was well known, as were assaults suffered and survived by Garrison.

Known for his uncompromising views, Rogers joined comrades like Stephen Symonds Foster and Parker Pillsbury in scathing criticism of the Christian church for waffling on slavery. Like other Garrisonians, he advocated the immediate and unconditional abolition of slavery and establishment of full rights for African Americans. Also like other radicals of his day, he believed in equality between men and women. In Pillsbury’s words, “Woman, to him, was in all rights, privileges and prerogatives, the full equal of man.”

An advocate of “non-resistance” and “moral suasion” as opposed to violence or political engagement, Rogers traveled alongside anti-slavery agitators like Pillsbury, Foster, Garrison, and Frederick Douglass, using his paper and his sharply worded articles to advance the cause. “He and his associates of the Garrison school of abolitionists relied solely on the power of moral and spiritual truth to rescue the slave as well as to redeem and save the world,” Pillsbury later wrote.

Rogers “annoyed his more conservative New Hampshire colleagues with his hard-hitting attacks on the church, his support for women’s rights, and his condemnation of ‘color-phobia,’” says Stacey Robertson, Pillsbury’s biographer.

He was also known as a “no organization” man. As Dorothy Sterling puts it in her biography of Abby Kelley, “At meetings he objected to the preparation of an agenda or the election of officers and insisted that anyone could speak on any topic at any time.”

Holding that any degree of coercion was a form of violence, “Rogers distrusted anyone in a position of authority, including ministers and priests, politicians and bureaucrats,” says Robertson. It was that principle which got him in trouble when his views began to depart from those of other leading abolitionists, also prone to factional infighting. When the NH Anti Slavery Society voted in 1844 that Herald of Freedom was the Society’s organ, not that of Rogers, Rogers took the Society’s name off the paper’s masthead and substituted that of John R French, who was serving as publisher and was engaged to Rogers’ daughter. When the Society’s board insisted on ownership, Pillsbury was installed as editor.

Rogers instead tried to start a new paper, The Herald of Freedom, but it was short-lived. Two years later he was dead, perhaps an after-effect of abdominal injuries he suffered playing football in his days at Dartmouth.

The office of Herald of Freedom was in The Stickney Block on North Main Street in Concord, an office building that no longer exists.

Nathaniel Peabody Rogers is buried in the Old North Cemetery in Concord.

A historic plaque can be seen at the Silver Cultural Arts Center at Plymouth State University, which sits where the Rogers home once stood.